Click here to see all images

May, 2017

Case of the Month

Clinical History:A 47-year-old man presented with progressive cough over the past 2 months, associated with fatigue, fever and dyspnea. He had failed to respond to antibiotics, and extensive work-up for infection was negative. Chest imaging showed diffuse bilateral airspace opacities and consolidation. Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) were reportedly negative. A surgical lung biopsy was performed (Figures 1-6).

Quiz:

Q1. The primary site of the injury in this process is:

- Airways

- Pleura

- Main pulmonary artery

- Medium and small vessels

- Lymphatics

Q2. What radiologic findings do you expect with these histologic findings?

- Dense lobar consolidation

- Bilateral cavitary nodules

- Reticular opacities with lower lobe honeycombing

- Tiny reticulonodular densities along a lymphatic distribution

- Solitary pure ground glass nodule

Q3. The most typical form of renal involvement in this condition is:

- Collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules

- Focal segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis

- Wire loop lesions

- Interstitial fibrosis and arterial hyalinosis

Q4. What percentage of patients with active multi-system granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) have a negative ANCA?

- None

- 3%

- 30%

- 70%

- 100%

Answers to Quiz

Q2. B

Q3. C

Q4. B

Diagnosis

Discussion

Classically, GPA causes necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the upper and lower respiratory tract with necrotizing vasculitis involving the small and medium vessels, and renal involvement in the form of focal segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Other frequent manifestations include ocular/orbital vasculitis and pulmonary capillaritis with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Clinically, GPA may have a highly variable presentation, and may present with organ-limited disease confined to the upper or lower respiratory tract, or the eye. Pulmonary imaging studies may show a variety of findings, including bilateral angiocentric nodules which may be cavitary, multiple ground glass opacities, pleural opacities, or multiple areas of nodular consolidation. Most (90%) of patients with systemic GPA will have PR3-ANCA, whereas 7% have MPO-ANCA, and the remainder (3%) are ANCA negative. However, the rate of ANCA negativity is much higher in organ-limited disease, including disease limited to the lung, as was illustrated in this case, where up to 50% of patients can have a negative ANCA.

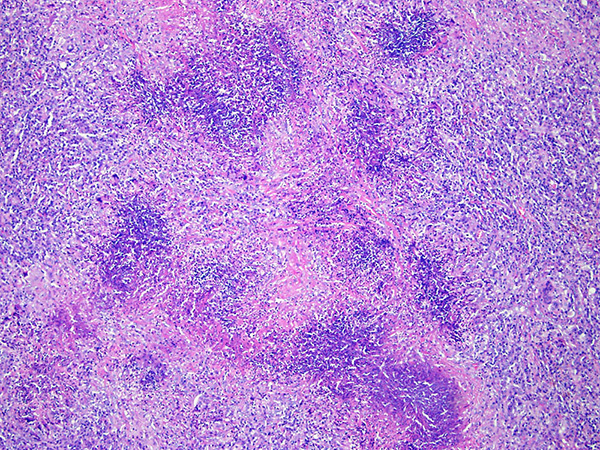

In this case, Figure 1 illustrates large nodular areas of basophilic geographic necrosis on low power. At higher power, the basophilic areas consist of necrotic neutrophils and nuclear debris, and neutrophilic microabscesses are common (Figure 2). At the edge of these necrotic areas, there are palisading histiocytes and scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3). The multinucleated giant cells of GPA often have a distinctive appearance, with syncytial-like nuclei showing angulated edges arranged in a horseshoe at the periphery of the cell (Figure 5). The chromatin tends to appear smudged and remarkably hyperchromatic, and these giant cells often stand out at low power. Figures 5 and 6 highlight vasculitis of medium-sized vessels characterized by transmural necrotizing inflammation with variable giant cells. These findings are diagnostic of GPA.

The most important differential diagnosis is infection. To maximize the yield thorough histologic examination should be performed, along with special stains such as Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS) and a stain for for acid fast bacilli (AFB). Incorporation of clinical and imaging findings is important, along with microbiologic data (cultures and serology). While infectious granulomas tend to have a more eosinophilic quality to the necrosis there is histologic overlap. An abundance of small non-necrotizing granulomas admixed with necrotizing granulomas would also be unusual in GPA, and would tend to favor infection, since the granulomas of GPA typically rim the areas of necrosis. Aspiration could be considered in the differential diagnosis, since necrotizing granulomas can be observed. However, aspiration tends to be more bronchiolocentric in distribution, and careful examination often reveals aspirated foreign material. Rheumatoid nodules could also be considered, but often have more eosinophilic necrobiotic areas, and could be further be excluded by correlation with clinical history, as most patients with pulmonary rheumatoid nodules have a long standing history of rheumatoid arthritis. Classical cases of sarcoidosis are composed exclusively of non-necrotizing granulomas, and thus can be easily differentiated from GPA. However, some cases of sarcoidosis can have small areas of necrosis, which can be misleading. The predominance of non-necrotizing granulomas in a lymphangitic distribution with hyalinized lamellar fibrosis would support sarcoidosis.

Take home message for trainees: GPA can be diagnosed on the basis of histology alone (even if ANCA is negative) provided that necrotizing granulomas with basophilic necrosis are seen along with necrotizing vasculitis.

References

Gómez-Gómez A, Martínez-Martínez MU, Cuevas-Orta E, Bernal-Blanco JM, Cervantes-Ramírez D, Martínez-Martínez R, Abud-Mendoza C. Pulmonary manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Reumatol Clin. 2014; 10(5):288-93.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013; 65:1–11.

Mukhopadhyay S, Wilcox BE, Myers JL, Bryant SC, Buckwalter SP, Wengenack NL, Yi ES, Aughenbaugh GL, Specks U, Aubry MC. Pulmonary necrotizing granulomas of unknown cause: clinical and pathologic analysis of 131 patients with completely resected nodules. Chest. 2013 Sep; 144:813-24.

Smith ML. Pathology of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Pulmonary and Renal Disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017 Feb; 141:223-231.

Contributors

Fellow in Surgical Pathology

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Jennifer M. Boland, M.D

Associate Professor

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA