Click here to see all images

March, 2018

Case of the Month

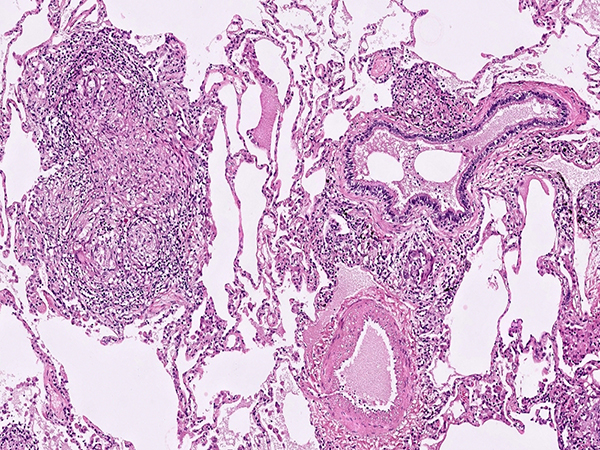

Clinical History:A 70 year-old male lifelong non-smoker presented to his pulmonologist with a 9 month history of progressive shortness of breath. The patient lives on a farm in rural New England where he gardens, hikes and clears trails, works with hay and horses, and uses a hot tub for muscle aches. Computed tomography scan demonstrated bilateral ground glass opacities with multiple small pulmonary nodules (Figure 1). Representative images from the right upper lobe wedge resections are shown (Figures 2-6).

Quiz:

Q1. The predominant cellular process seen in these sections are:

- Lymphoid aggregates

- Eosinophilic infiltrates

- Organizing pneumonia

- Granulomas

- Fibroblastic foci

Q2. What is the most typical radiologic distribution for this disease process demonstrated in these histologic images?

- Mostly lower lobes and subpleural involvement

- Upper lobe ground glass opacities with small centrilobular nodules

- Peribronchovascular and pleural distribution with mediastinal lymphadenopathy

- Asymmetrical single lobe involvement

- Interlobular septal line thickening with ground glass opacities (crazy-paving pattern)

Q3. What disease process would generally NOT be included in the differential diagnosis?

- Sarcoidosis

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Berylliosis

- Pulmonary involvement by IBD/Crohn’s disease

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP)

Q4. When presented with this tissue pattern in the lung, which stains would be the most appropriate to order?

- CD68 and CD1a immunohistochemistry

- Gram stain

- GMS and AFB stains

- Trichrome and elastic stains

- CD3 and CD20 immunohistochemistry

Answers to Quiz

Q2. B

Q3. E

Q4. C

Diagnosis

Discussion

Hot-Tub Lung (HTL) a relatively rare but important diagnostic consideration when faced with a diffuse pulmonary parenchymal granulomatous reaction in immunocompetent patients. HTL is caused by inhalation of water aerosol containing non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), with most cases belonging to the Mycobacterium avium complex family. There is still debate as to whether HTL represents more of an infectious process or conversely a hypersensitivity reaction to the inhaled NTM organisms. This is mirrored by the histologic presentation that shares hybrid features of both an infectious granulomatous process as well as more traditional hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP).

The most salient histologic finding is that of moderately well-formed largely non-necrotizing granulomas in a random, airspace, or bronchiolocentric distribution. The granulomas are generally larger and more well-formed than the “small poorly formed non-necrotizing granulomas” of HP. Necrosis is very rarely encountered in HTL (in contrast to infectious AFB or fungal infections). Exogenous or foreign polarizable materials within the granulomas, if present, would point to an aspiration pneumonitis, pneumoconiosis, or injection/talc granulomatosis depending on the findings. The granulomas of sarcoidosis tend to be ever larger and more well-formed with concentric fibrosis, and have a lymphangitic distribution (lymph node involvement plus pleural, septal, and peribronchovascular distribution). As with any interstitial lung disease, the proper clinical and radiologic context is extremely important in arriving at the correct diagnosis.

In addition to correlating the suggestive histologic findings with the clinical presentation and exposure history, the diagnosis of HTL can be supported if NTM organisms are detected in the tissue by either microbiologic cultures and/or PCR based methods. The ultimate diagnostic coup de grace can be achieved by eliciting a temporally aligned hot tub exposure history along with NTM isolates obtained from said hot tub water.

Like HP, treatment of HTL is largely avoidance of the inciting agent (NTM contaminated hot-tub), although steroids are also generally used to provide symptomatic relief.

Take home message for trainees: HTL is a rare form of granulomatous lung disease that shares features of both an infectious process and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Appropriate clinical history and microbiologic testing are keys to establishing this diagnosis.

References

Donato J, Phillips CT, Gaffney AW, VanderLaan PA, Mouded M. A case of hypercalcemia secondary to hot tub lung. Chest. 2014;146:e186-e189.

Mukhopadhyay S , Gal AA . Granulomatous lung disease: an approach to the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134: 667-90.

Verma G, Jamieson F, Chedore P, Hwang D, Boerner S, Geddie WR, Chapman KR, Marras TK. Hot tub lung mimicking classic acute and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: two case reports. Can Respir J. 2007;14:354-6.

Khoor A, Leslie KO, Tazelaar HD, Helmers RA, Colby TV. Diffuse pulmonary disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent people (hot tub lung). Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:755-62.

Contributors

Director of Thoracic Pathology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA