Click here to see all images

September, 2025

Case of the Month

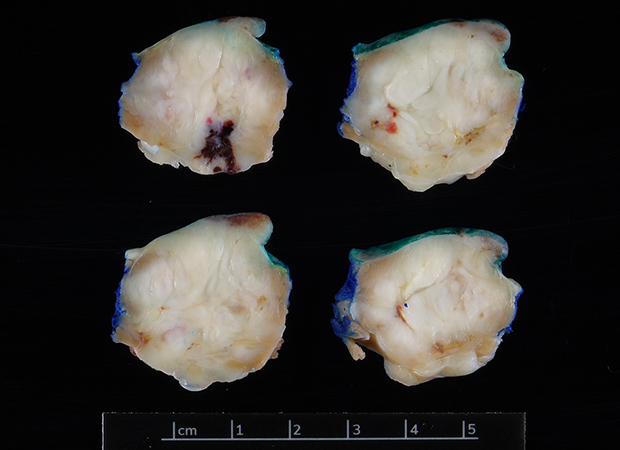

Clinical History:A 32-year-old male with a history of 4.8 cm oval enhancing mass of right lower extremity diagnosed as a malignant tumor underwent below-knee amputation, four years ago at an outside hospital. After undergoing a 6-month oncology surveillance protocol, three years later on the CT scan of the chest demonstrated enlarging bilateral lung nodules, largest in the right upper lobe, 2.6 cm suggestive of metastatic disease. A 2.6 cm right ventricular mass was also noted on trans-thoracic echocardiogram. Following a CT-guided biopsy of right upper lobe nodule, he underwent wedge resection of right upper lobe mass (Figure 1) along with wedge resection (x3) of the left lower lobe masses with surgical resection of the right ventricular mass (Figure 2). Histologic sections show a biphasic neoplasm with spindle and epithelioid cells (Figures 3-4). On immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic cells show strong expression for SOX10 (Figure 5), patchy expression for HMB 45 (Figure 6), while no expression for pan-keratin (AE1/AE3), keratin 8/18, SMA, TFE-3 and PRAME-3 were seen.

Q1. Based on the H&E appearance of this biphasic/spindle cell neoplasm, the differential diagnosis includes which of the following?

- Malignant melanoma

- Epithelioid sarcoma

- Synovial sarcoma

- Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue

- All of the above

Q2. The immunohistochemical profile of this lesion is best suited to which of the following?

- Malignant melanoma

- Epithelioid sarcoma

- Synovial sarcoma

- Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) results came back abnormal and demonstrates EWSR1 rearrangements (majority of the cells demonstrate both copies rearranged).

Q3. Which of the following show EWSR1 rearrangement on FISH studies?

- Malignant melanoma

- Epithelioid sarcoma

- Synovial sarcoma

- Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue

Answers to Quiz

Q1. E

Q2. D

Q3. D

Q2. D

Q3. D

Diagnosis

Metastatic Clear Cell Sarcoma to the Lung

Discussion

While the incidence of the Clear cell sarcoma (CCS) of soft tissue is <1% of all soft tissue sarcomas, first described by Enzinger in 1965, it is clinically aggressive with frequent local recurrence and late metastases, most often to lung and regional lymph nodes. Cardiac metastases are extremely rare and signify advanced disease.

Histologically, CCS is characterized by nests and fascicles of spindle and epithelioid cells separated by fibrous septa, often with clear to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. The expression of melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX10, HMB45 and Melan-A are similar to malignant melanoma. By comparison, keratin positivity with loss of INI1/SMARCB1 expression is seen in epithelioid sarcoma. Given the biphasic morphology and keratin positivity, biphasic synovial sarcoma should also need to be considered. Metastases to lungs develop in up to 50% of cases. In synovial sarcoma, FISH or NGS may be pursued to confirm the specific t(X;18) translocation, which results in the fusion of two genes, SS18 at 18q11(previously designated SYT) and SSX at Xp11. However, recently established SS18-SSX fusion specific immunohistochemical antibody has been routinely used as a surrogate now. PRAME (Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) is positive in around 80% of malignant melanomas and around 95% of metastatic melanomas, while clear cell sarcomas are consistently reported negative as CCS and malignant melanoma are often histologically indistinguishable. If in doubt, testing for the pathognomonic EWSR1 gene rearrangement, most commonly EWSR1–ATF1 [t(12;22)(q13;q12)], and less often EWSR1–CREB1 [t(2;22)(q34;q12)] confirms the diagnosis and excludes the histologic mimics. It highlights the importance of combining histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular data in differentiating CCS from its mimics, especially in metastatic disease settings.

Take-home message for trainees:

The differential diagnosis for metastatic biphasic neoplasms in the lung is broad. Reviewing the patient's previous pathology slides and additional molecular studies are particularly helpful. PRAME appears to be a useful marker for excluding a diagnosis of malignant melanoma.

Histologically, CCS is characterized by nests and fascicles of spindle and epithelioid cells separated by fibrous septa, often with clear to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. The expression of melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX10, HMB45 and Melan-A are similar to malignant melanoma. By comparison, keratin positivity with loss of INI1/SMARCB1 expression is seen in epithelioid sarcoma. Given the biphasic morphology and keratin positivity, biphasic synovial sarcoma should also need to be considered. Metastases to lungs develop in up to 50% of cases. In synovial sarcoma, FISH or NGS may be pursued to confirm the specific t(X;18) translocation, which results in the fusion of two genes, SS18 at 18q11(previously designated SYT) and SSX at Xp11. However, recently established SS18-SSX fusion specific immunohistochemical antibody has been routinely used as a surrogate now. PRAME (Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) is positive in around 80% of malignant melanomas and around 95% of metastatic melanomas, while clear cell sarcomas are consistently reported negative as CCS and malignant melanoma are often histologically indistinguishable. If in doubt, testing for the pathognomonic EWSR1 gene rearrangement, most commonly EWSR1–ATF1 [t(12;22)(q13;q12)], and less often EWSR1–CREB1 [t(2;22)(q34;q12)] confirms the diagnosis and excludes the histologic mimics. It highlights the importance of combining histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular data in differentiating CCS from its mimics, especially in metastatic disease settings.

Take-home message for trainees:

The differential diagnosis for metastatic biphasic neoplasms in the lung is broad. Reviewing the patient's previous pathology slides and additional molecular studies are particularly helpful. PRAME appears to be a useful marker for excluding a diagnosis of malignant melanoma.

References

1. Enzinger FM. Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47(4): 772–779.

2. Miettinen M, ed. Modern Soft Tissue Pathology: Tumors and Non-Neoplastic Conditions. Cambridge University Press; 2016.

3. Zaborowski M, Vargas AC, Pulvers J, et al. When used together SS18-SSX fusion-specific and SSX C-terminus immunohistochemistry are highly specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma and can replace FISH or molecular testing in most cases. Histopathology.2020;77(4):588-600.

4. Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Toland A, et al. Diffuse PRAME expression is highly specific for malignant melanoma in the distinction from clear cell sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2020 Dec;47(12):1226-1228.

2. Miettinen M, ed. Modern Soft Tissue Pathology: Tumors and Non-Neoplastic Conditions. Cambridge University Press; 2016.

3. Zaborowski M, Vargas AC, Pulvers J, et al. When used together SS18-SSX fusion-specific and SSX C-terminus immunohistochemistry are highly specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma and can replace FISH or molecular testing in most cases. Histopathology.2020;77(4):588-600.

4. Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Toland A, et al. Diffuse PRAME expression is highly specific for malignant melanoma in the distinction from clear cell sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2020 Dec;47(12):1226-1228.

Contributors

Raghavendra Pillappa, MBBS, MD

Staff Pulmonary Pathologist

Associate Director, Immunohistochemistry

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Los Angeles, CA

Staff Pulmonary Pathologist

Associate Director, Immunohistochemistry

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Los Angeles, CA