Click here to see all images

November, 2025

Case of the Month

Clinical History:A 32-year-old woman, with no history of smoking or significant medical conditions, presented to a regional hospital with cough, dyspnea, and chest pain. Chest X-ray revealed a right-sided pneumothorax, which was managed with a thoracic drain. The patient experienced recurrence a few weeks later, followed by a third episode a month after. She was referred to a tertiary care center, where she underwent right video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Examination revealed a bleb in the middle lobe, prompting blebectomy. During the procedure, a violaceous pedunculated polyp (Figure 1) was found on the diaphragm, excised, and a subtotal parietal pleurectomy with pleurodesis was performed.

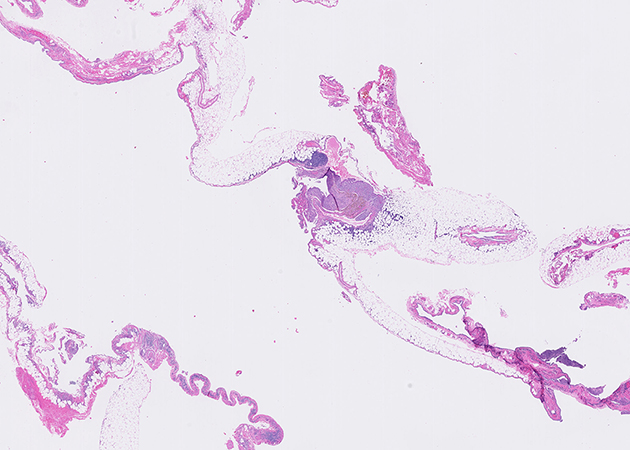

Representative H&E histological images of the pleurectomy specimen are shown in Figures 2 to 4 (1X and 20X magnification) and immunohistochemical stains for CD10 and estrogen receptor performed on the area of Figure 4 are presented in Figures 5 and 6, respectively. The diaphragmatic pedunculated polyp was composed of fibroadipose tissue with multifocal nodules with similar histological features as Figure 4 (not shown).

Q1. Based on the clinical information provided, which of the following lesions most likely explains the violaceous pedunculated polyp observed on the diaphragm (Figure 1)?

- Hemangioma

- Solitary fibrous tumor

- Well-differentiated papillary mesothelial tumor

- Endometriosis implant

Q2. Which of the following diagnoses is not part of the usual clinical manifestations of thoracic endometriosis?

- Pneumothorax

- Hemoptysis

- Pneumonia

- Hemothorax

Q3. Among women with endometriosis-related catamenial pneumothorax, which of the following pathologic finding is more commonly seen in endometriotic lesions?

- Endometrial stroma

- Endometrial glands

- Endometrial glands and stroma

- Bullae and/or bleb

Answers to Quiz

Q1. D

Q2. C

Q3. A

Q2. C

Q3. A

Diagnosis

Thoracic endometriosis in the context of catamenial pneumothorax

Discussion

Low-power histological examination of the pleurectomy specimen (Figure 2) reveals fragments of fibro-adipose tissue covered by a layer of mesothelial cells with focal reactive proliferations (Figure 3). The fragments contain scattered, more densely cellular nodules. Examination at higher magnification reveals the nodules are composed of densely packed small round to ovoid cells with thin-walled capillaries and extravasated red blood cells. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages are evident (Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the round cells were positive for CD10 and estrogen receptor (Figures 5 and 6), consistent with endometrial stromal cells and supporting the diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis. Endometrial glands were not seen. The diaphragmatic pedunculated polyp was similarly diagnosed as an endometriosis implant (Question 1).

Catamenial pneumothorax (CP) is a recognized cause of pneumothorax in females of reproductive age, but its clinical context and management are still poorly described. It is defined as recurrent pneumothorax occurring between the day prior to and within 72 hours after the onset of menses, a temporal relationship that was confirmed upon further questioning of the patient in this case. The actual incidence of the disease is unknown, but CP is the most frequent clinical manifestation of thoracic endometriosis. Less common presentations include hemoptysis, hemothorax, and thoracic endometriotic nodules (Question 2). In women of reproductive age with surgically treated pneumothorax, CP occurs in up to 35% of cases, with over 90% being right-sided. Diaphragmatic lesions, including perforations, endometriotic implants, and nodules, are observed in approximately 90% of patients.

Histological confirmation of thoracic endometriosis is variable in CP (reported between 39-88% of cases), while pelvic endometriosis is identified in about half of cases. Thoracic endometriotic lesions most commonly involve the diaphragm, followed by the visceral and parietal pleura. Pathological criteria for thoracic endometriosis include the presence of endometrial glands, stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages, but the presence of endometrial stroma alone with positive immunohistochemical staining for CD10 and estrogen receptor is sufficient for diagnosis. In CP cases with histologically confirmed endometriosis, endometrial stroma is the most common finding, followed by glands and hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Question 3). Although bullae are typically associated with non-catamenial pneumothorax, they are found in approximately 40% of women with CP. The appropriate clinical management is still uncertain with recurrences occurring in approximately one-third of cases, despite surgery and hormonal therapy.

Take-home message for trainees:

Thoracic endometriosis should be actively sought in reproductive-aged women with recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraxes undergoing surgical management. Histological diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis requires the presence of both endometrial glands and stroma, or endometrial stroma alone with positive immunohistochemical staining for CD10 and estrogen receptor.

Catamenial pneumothorax (CP) is a recognized cause of pneumothorax in females of reproductive age, but its clinical context and management are still poorly described. It is defined as recurrent pneumothorax occurring between the day prior to and within 72 hours after the onset of menses, a temporal relationship that was confirmed upon further questioning of the patient in this case. The actual incidence of the disease is unknown, but CP is the most frequent clinical manifestation of thoracic endometriosis. Less common presentations include hemoptysis, hemothorax, and thoracic endometriotic nodules (Question 2). In women of reproductive age with surgically treated pneumothorax, CP occurs in up to 35% of cases, with over 90% being right-sided. Diaphragmatic lesions, including perforations, endometriotic implants, and nodules, are observed in approximately 90% of patients.

Histological confirmation of thoracic endometriosis is variable in CP (reported between 39-88% of cases), while pelvic endometriosis is identified in about half of cases. Thoracic endometriotic lesions most commonly involve the diaphragm, followed by the visceral and parietal pleura. Pathological criteria for thoracic endometriosis include the presence of endometrial glands, stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages, but the presence of endometrial stroma alone with positive immunohistochemical staining for CD10 and estrogen receptor is sufficient for diagnosis. In CP cases with histologically confirmed endometriosis, endometrial stroma is the most common finding, followed by glands and hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Question 3). Although bullae are typically associated with non-catamenial pneumothorax, they are found in approximately 40% of women with CP. The appropriate clinical management is still uncertain with recurrences occurring in approximately one-third of cases, despite surgery and hormonal therapy.

Take-home message for trainees:

Thoracic endometriosis should be actively sought in reproductive-aged women with recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraxes undergoing surgical management. Histological diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis requires the presence of both endometrial glands and stroma, or endometrial stroma alone with positive immunohistochemical staining for CD10 and estrogen receptor.

References

Alifano M, et al. Catamenial and noncatamenial, endometriosis-related or nonendometriosis-related pneumothorax referred for surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176(10):1048-53.

Ghigna MR, et al. Thoracic endometriosis: clinicopathologic updates and issues about 18 cases from a tertiary referring center. Ann Diagn Pathol 2015;19(5):320-5.

Gil Y, Tulandi T. Diagnosis and Treatment of Catamenial Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(1):48-53.

Legras A, et al. Pneumothorax in women of child-bearing age: an update classification based on clinical and pathologic findings. Chest 2014;145(2):354-360.

Visouli AN, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6(Suppl 4):S448-60.

Ghigna MR, et al. Thoracic endometriosis: clinicopathologic updates and issues about 18 cases from a tertiary referring center. Ann Diagn Pathol 2015;19(5):320-5.

Gil Y, Tulandi T. Diagnosis and Treatment of Catamenial Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(1):48-53.

Legras A, et al. Pneumothorax in women of child-bearing age: an update classification based on clinical and pathologic findings. Chest 2014;145(2):354-360.

Visouli AN, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6(Suppl 4):S448-60.

Contributors

Michaël Maranda-Robitaille, MD MSc

Postgraduate year 3, Diagnostic and Molecular Pathology

Laval University

Quebec City, Quebec, Canada

Andréanne Gagné, MD PhD

Thoracic Pathologist and Assistant Professor

Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec –

Université Laval (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute – Laval University)

Quebec City, Quebec, Canada

Postgraduate year 3, Diagnostic and Molecular Pathology

Laval University

Quebec City, Quebec, Canada

Andréanne Gagné, MD PhD

Thoracic Pathologist and Assistant Professor

Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec –

Université Laval (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute – Laval University)

Quebec City, Quebec, Canada